Sometimes my vocabulary makes me cringe.2

Five centuries ago to be a witch my legs would have been crushed […] We continue to live in a world where such judgement is conducted across tear gas tables, where there continues to exist the dianoetic drills of torment, where body parts are exposed to photo-disintegration.3

In the film Pontypool (2008), the character Grant Mazzy, a radio DJ and shock-jock, uses every opportunity he can to deliver righteous diatribes on the air, and gradually it turns out they might be warranted. Over the course of the film it is slowly revealed that a virus which turns people into zombies has infected certain English words. The virus infects people when they understand the word. Realizing this, Mazzy goes off on one. He says nothing has changed, he says it’s the same as every other day. He claims that benign phrases uttered every day by most people such as ‘Good morning’ actually ‘contain Armageddon’. In order to delay or avert infection from the language virus, characters try to dislodge the meanings of certain words—for example, by repeating a word until it is meaningless as some kind of immune response, though this usually fails—or they imitate the sounds around them like kettles whistling, or they swap one meaning for another, insisting to each other that ‘kill’ means ‘kiss’. To help people avert infection, Mazzy begins revising the meaning of many words and spouting incomprehensible nonsense into the microphone. ‘I don’t think we’re saving the world with shitty haiku’, Sydney Briar says to Mazzy in response.

This could also be understood as a negative response to a question which was everywhere in poetry circles around the 2010s – what can poetry do? And can it do anything politically? Bonney was obsessed with this question, and indeed co-organized some conferences on the topic.4 This essay is partly about a situation in which what words mean becomes vital, a matter of life and death. I initially drafted this in late 2020, and since then Danny Hayward has published a really useful analysis of Bonney’s work which also identifies revising the definitions of words as something ‘essential to his poetry.’5 This essay offers another exploration of this central component of Bonney’s work by reading ‘What Teargas is For’ and ‘Further Notes on Teargas’, both published in 2016 and then collected in Our Death (2019). I am going to have to move across a wide range of material, from films and albums to literary criticism and entire poetic oeuvres, because I am going to have to describe some of the associative leaps Bonney’s work makes. At times this results in a certain density of expression, though it is still considerably less dense than the original material’s frequent clusters of proper names and specific artworks and its distillations of centuries of thought. I want to bring the sometimes immense gulfs across which Bonney’s thinking discharges its most illuminating and thrilling sparks into relief, rather than smooth them over.

The Cloud of Unknowing, esoteric poetry, and magic

I’m interested in moments where mysticism and occultism emerge in Bonney’s work. I’d like to start with a passage from ‘Letter Against the Language’ which opens Our Death:

I guess you must be familiar with his [Pier Paolo Pasolini’s] unfinished St Paul screenplay – the bit where he quotes Corinthians on ‘hearing inexpressible things, things we are not able to tell’. I got really obsessed with that for a while. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not about to disappear into some kind of cut-rate Cloud of Unknowing, or worse, some comfortably opaque experimental poetry. I mean, fuck that shit. In the last essay he wrote, Pasolini made it pretty damn clear what might be implied by ‘inexpressible things’, things ‘we are not able to tell’. It is names. ‘I know the names’, he wrote, in that essay published in 1974. The names of those who sit on the various committees. The ‘names of those responsible for the massacres’. The names of power. The forbidden syllables. The names of those whose names it is impossible to pronounce in certain combinations and continue simply to live. And obviously, this has very little to do with what certain idiots still call ‘magic’, which means it has everything to do with it.6

The text here attributes to the reader familiarity with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work, in particular a then-recently translated screenplay. The speaker, who is never quite (though always almost) Sean Bonney himself, says that they were ‘obsessed’ with a passage which invokes ineffability.7 Next, we as readers are assured that the speaker will not become enveloped by a ‘Cloud of Unknowing’, which would, it is implied, be a bad thing, but not as bad as turning to ‘comfortably opaque experimental poetry’. I will discuss The Cloud of Unknowing in greater detail when it appears again in ‘What Teargas is For’. By using this second term, ‘comfortably opaque experimental poetry’, Bonney’s letter warns the reader against the dangers of experimental work which completely eschews sense but also remains ‘comfortable’ – perhaps what the letter has in mind is the sound poetry of Bob Cobbing, which was hugely influential on Bonney, but was not where his own trajectory took him.8 A discounted mysticism should be eschewed, the letter says, but what would be worse is composing experimental work which does not risk anything – including, presumably, the risk of being accused of being a discounted or ‘cut-rate’ mystic. By the end of the quote, the letter has made a strong distinction between what Pasolini is talking about and ‘what certain idiots still call magic’, only to insist that nonetheless magic must be kept in mind while thinking about Pasolini’s invocation of ineffability and the names of the rich and powerful.

To further unpack the brief discussion of ‘magic’ in ‘Letter Against the Language’, I’d like to return to an earlier text. ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ consists of six blog posts published in 2012 and 2013. They offer a tight weave of Black Radical, Romantic, and European avant-garde traditions. The militant poetics of the title is the relation between the ‘real poetry of capital’ and the cries of those whom it crushes; the poetry that attempts to counter capital must be understood as an expression of capital itself.9 ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ is highly dialectical in this regard, offering a description of the poetics of capital (zero-hours contracts, workfare, the sentences doled out by judges, and the actions of the police) rather than a description of a poetics in opposition to capital.10 Capital’s poetics is opposed by a submerged poetics exemplified for Bonney by George Jackson’s prison letters, but these letters must also always be considered to be inside the ‘prosody’ of the judge whose sentence Jackson is serving.11 Jackson is forced into a militant position by this relation to the judge. It is not that one pole of the judge-Jackson relation must be celebrated and valorised further; the relation itself must be destroyed.

On 26th July 2019, Bonney put four essays up on a blog called ‘round midnight: notes and essays on militant poetics’. Many of the essays ruminate over the same issues and raw material discussed in the ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ six or seven years earlier.12 On the blog, Bonney develops and deepens his repertoire. Incessantly plaiting the same quotations through each other in new arrangements, Bonney’s argument orbits them as they intertwine. These quotations are Bonney’s musical notes. He explores what happens between them by placing them in various constellations to find adjacent feelings, adjacent meanings. The notes build to chords, and these chords get at new tones. The time of posting is not visible on the blog, but the first essay to appear when I visit it online is ‘Baraka and Surrealism’, which opens with a question about magic. Bonney asks ‘what value’ the ‘metaphors’ of ‘the word as magic, and the poet as magician’ may ‘still have as a revolutionary poetics.’13 Magic elevates mimesis to praxis. Mimesis partakes in magical thinking, which is the belief that thoughts and desires can transform and/or directly transfer themselves to the material world, other people, or the future. Many of the swarm of thinkers who laboured under the later label ‘modernism’ engaged with the occult to invigorate the relation between the world and representation; magic offered a way of reconceptualising mimesis because occultists and magicians ‘understood that the mimetic is able to produce, not just an inert copy, but an animated copy powerful enough to enact change in the original.’14 Although magic is part of countercultural tendencies and therefore frequently read as anticapitalist, for Bonney, magic is a word and a practice which has no inherent qualities and is frequently used by capital and the ruling classes.15 The poems I am going to analyse with regards to mysticism are particularly alert to mysticism’s fungibility, by which I mean the ways in which it can be used by those in power as well as the less powerful. A magic where mimesis shapes social reality is not only localizable to counter-hegemonic artworks or protests, but is present in contracts, courtrooms, board meetings, and advertising billboards.16 Folding together ideas like hegemony, performative utterances, and spells, ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 1/3’ decries advertising and hate-speech directed against the poor (as exemplified by The Daily Mail’s attacks on so-called ‘dole scroungers’) as spells, claiming that these must be countered by ‘the poetic hex.’17 Many poets have taken this up, most notably Verity Spott, in works such as Gideon (2014) and We Will Bury You (2017). Bonney’s interest in magic, witches, the tradition of the Ranters, and counterculture in general is longstanding and intimately linked to a project invested in recovering parts of history which are submerged and excluded. That exclusion is part and parcel of the formation of a hegemonic colonial and self-describing ‘rational’ philosophical tradition in the ‘West’. Recovering these traditions is difficult terrain to negotiate, full of potential pitfalls.

This might be linked to another undercurrent in ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’: how can one speak of communism or revolution from inside capitalism? As Bonney puts it: ‘Attempts to deal with the necessities of speech and cognition from within a place where they are made impossible is a defining theme throughout revolutionary poetics, from Milton through Blake and Shelley, and via Marx into the radical avant-gardes of the early twentieth century’.18 How is it possible to adequately express revolt when so much language is thoroughly permeated with the hegemony of the ruling class? Bonney’s ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ amps this tension up until it feels like a contradiction – it is, as the previous quote states, ‘made impossible’. Some tactics to overcome this contradiction might be characterized as esoteric, with an emphasis on hiding things and on secret codes, or as mystical, emphasizing ineffability, refusing to speak, and going beyond language. These two approaches appear regularly in Bonney’s work. In the ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2/3’, Bonney derides the ‘reactionary esotericism’ of critical remarks by George Steiner and Mario Vargas Llosa about the mystery and unknowability of the poetry of Paul Celan and César Vallejo. For Bonney, such remarks ‘conceal the social pain’ that is contained in Celan and Vallejo’s work.19 The risks get higher, as esoteric readings of these poets and indeed capital can not only be reactionary but also express the hidden content of fascism. Bonney writes: ‘If esoteric poetry is potentially the unspoken expression of the destruction of capitalism, then it is just as potentially the unspoken expression of the fascism that is always lurking at capital’s centre’.20 The workings of Capital are esoteric too, and its secrets must be revealed. Bonney wants poetry to become ‘prior to itself’ and to ‘force that “secret” into the raw light of day’ – the ‘secret’ being all of those who have been ‘left out’ of ‘bourgeois reality.’21 What happens when language and thought move outside of what is approved, readily accessible, or hegemonic? Screams, music, and static rather than words and language are where Bonney goes to describe revolt and a future worth fighting for.22 Of course, what is called ‘mystical’ is often simply being denigrated as nonsense, and nonsense is often what a code can look like to someone without the ability to crack it, so these elements often coagulate in Bonney’s work.

Knowing and Understanding

The final instalment of ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ was ‘Further Notes on Militant Poetics’ and it begins with an extrapolation from Walter Benjamin’s essay on Surrealism. In paraphrase of Marx’s ‘Afterword to the Second German Edition’ of Capital, Volume One from 1873, Bonney suggests that, for Benjamin, the crisis of the 1930s would ‘reveal the rational kernel of poetic mysticism.’23 For Bonney there is in ‘poetic mysticism’ a ‘rational kernel’. Although he is citing Benjamin, he is echoing Marx, who uses this same phrase when he speaks about turning Hegel’s dialectic ‘right side up’ to ‘discover the rational kernel in the mystical shell.’24 Mysticism is frequently bound up with confusion and nonsense. In the Appendix to the English edition of Capital, Volume One Marx attempts to disentangle some of Proudhon’s ideas, saying they are a product of ‘confusion’ and a kind of ‘nonsense.’25

In the fiftieth section of Kant’s Critique of Judgement (1790) called ‘Of the combination of Taste with Genius in the products of beautiful Art’, Kant writes: ‘Abundance and originality of Ideas are less necessary to beauty than the accordance of the Imagination in its freedom with the conformity to law of the Understanding. For all the abundance of the former produces in lawless freedom nothing but nonsense; on the other hand, the Judgement is the faculty by which it is adjusted to the Understanding’.26 If the faculty or capacity of imagination is expressing without restraint, it proliferates and spreads uncontrollably. We might colloquially say that it is ‘running riot’. Kant seeks to discipline this ‘lawless freedom’. While Bonney does not explicitly comment on this passage from Kant, the quotation I am going to analyse from Bonney below shares some characteristic tendencies with Fred Moten’s incisive and influential discussion of this passage from Kant in Stolen Life (2018), which is itself indebted to Winfried Menninghaus’s In Praise of Nonsense: Kant and Bluebeard (1999). Commenting on Kant’s passage, Moten notes that ‘Law enforcement, in whatever exclusionary attempt to ensure equilibrium, belatedly responds to what shows up as (de)generative dehiscence requiring suture and irregular wholeness in need of incision.’27 This ‘law enforcement’ calls attention to the ways in which production of meaning is regulated.28

‘What Teargas is For’ continues the playful examination, in the ‘Letters’ in general, of the relation between understanding and knowing and not knowing, and how this changes in situations of antagonism.29 At one point in ‘Letter on Harmony and Sacrifice’ (2012), understanding and knowledge – between which there are subtle distinctions, but which nonetheless are constantly blurred – are likened to a bullet. Bonney thinks about what understanding is by relating it to the climax of Lindsay Anderson’s film if… (1968), in which a schoolmaster is shot in the head by rebelling students:

Can you understand what I’m saying? Actually, I was talking to a friend a couple of days ago about what ‘understanding’ might actually mean. ‘Understanding’, he said, ‘is precisely what is incompatible with the bourgeois mind’. For some reason I started thinking about the final scene in Lindsay Anderson’s film If. You know it, of course – everybody does. Malcolm McDowell and his crew are sitting on the roof of the school, firing at all the teachers and parents and other kids, and then in a brief pause, the headmaster steps forward. He thinks he’s such a liberal, you recall. ‘Boys’, he implores. ‘boys – I understand you’. Yeh. And so the character played by Christine Noonan – one of the few characters in the film who isn’t a ‘boy’ – she shoots him right in the centre of his forehead. You know what I’m getting at – that bullet is his understanding, plain and simple, tho I’m not quite clear just how incompatible it is with the headmaster’s presumably bourgeois sense of beauty, love and imagination, or indeed his understanding, ultimately, of himself and of everything else – including his killer. A killer who is identified only as ‘the girl’ in the cast list, even tho she’s obviously the central figure in the film.30

The film if… takes its title from Rudyard’s Kipling’s classic stoic schoolboy verse ‘If –’. It thereby invokes a tradition of English literary imperialism and its relation to elite training.31 In the middle of this passage, the letter tells us that we ‘of course’ know the film, ‘everybody does’. This is an assumption about the reader, and about what everyone knows. It is deeply serious, insofar as Bonney is really claiming that everyone knows the film in the sense of knowing what the film and this scene is about. But also, it does not matter if we know it, because Bonney is about to summarize the bits he needs us to know about. ‘Letter on Harmony and Sacrifice’ says that understanding is a bullet, the death of the one who understands, which is potentially compatible with the understanding of the headmaster or bourgeois.

Jacob Bard-Rosenberg describes Bonney as an ‘untimely symbolist.’32 The Symbolists Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud were extremely important for Bonney. So was undoing the legacy of Kant. Bonney’s translations or versions of Rimbaud, Happiness: Poems After Rimbaud (2011) was published by Unkant publishers, whose whole purpose was to undo the legacy of Kant.33 Happiness is heavily influenced by Kristin Ross’s The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune (2007), a book which relates Rimbaud’s work to its political context and the Paris Commune.34 ‘Letter on Poetics (after Rimbaud)’ (2011) talks about this, describing Rimbaud’s derangement of the senses as the aesthetic correlate to a riot and the Commune itself: ‘“The long systematic derangement of the senses”, the “I is an other”, he’s talking about the destruction of bourgeois subjectivity, yeh? That’s clear, yeh?’35 In Bonney’s characterisation of Rimbaud’s poems of the Commune, we might read ‘bourgeois subjectivity’ as the mode of subjectivity enabled and created by Kantian theories of Understanding and Knowing. In 1871, the Commune emerged as a kind of rent-strike, taking over part of the city, before the communards were massacred, and the population disciplined. Two years after the Commune, Marx wrote a postface to Capital, Volume One, speaking of the mystical nature of the Hegelian dialectic.36 In Rimbaud, poetic Imagination ‘runs riot’, defying the regulative power of Kantian Understanding, just as the Communards defy the regulative powers of law enforcement. This has its counterpart in the disciplining of what are considered deviant forms of psychology, perhaps the worst being ‘mob psychology’. The disciplining of laws of association has a correlate in the disciplining of the mob, in the problem of disciplining the lower classes and those deprived of their own power. The ‘Letters’ are intimately intertwined with the riots of 2011, riots which erupted after yet another police murder – that of Mark Duggan in Tottenham, North London on 4 August 2011, about 2 miles from Bonney’s rented flat.37 It is not just that police violence and aesthetic concerns are insistently intertwined in the ‘Letters’ – it would be more accurate to say that Bonney’s work is in flight from the constant and always intertwining pathologizations of criminality and art, which we might grasp together in the word ‘understanding’. The work is in flight from modes of understanding which would seek to discipline, incarcerate, torture, or murder those pathologized subjects and objects. He writes in both excess of, and destitution from under and outside, any of the aesthetic and political regimes which need to either discipline or harness all manner of errancy –to subject ‘lawless freedom’ to the ‘law of understanding’ – in how people live and socialize.

‘What Teargas is For’

On 1st October 2016, Bonney posted ‘Our Death 12 /// What Teargas is For.’38 It begins with a gesture we have already discussed, an invocation of the reader’s knowledge. Bonney’s texts are always and generously expecting us to know or catch up with what he is saying. He apparently expects us to know who makes teargas and wants to reveal to us what it does, what it is for. The text mentions Westminster Group PLC, founded in 1988, which supplies weapons (in their parlance ‘systems and equipment’) to the domestic UK and international commercial marketplace. Westminster’s Non-Executive Chairman is Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Malcolm Ross, Master of the Household of the Prince of Wales. Teargas has been carefully designed to cause physical and psychological trauma and pain.

‘What Teargas is For’ invokes the tradition of Christian mysticism by referencing The Cloud of Unknowing, an anonymous spiritual guide addressed to a student written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century (see Fig. 1, below). That text argues that the way to know God is to abandon consideration of God’s particular attributes and surrender ourselves to the cloud of unknowing that hides God from any possible understanding. The aim of the contemplative experience is to know God, as much as possible, from within this cloud of unknowing.39 Knowledge is denigrated in The Cloud of Unknowing in favour of experience. The form of contemplation advocated by its author is not directed by the intellect. The important thing about this text in relation to ‘What Teargas is For’, I think, is that the cloud of unknowing is a guide to approaching the divine.

The poem depicts a situation and a dynamic. I want to first say something about what is not present. The text does not describe a riot or protest which has occasioned the firing of teargas, and this is important. The firing of teargas is arbitrary. The poem refuses to imply that it has been fired at any point in the past because of something a crowd has done, or even that it might be used in this manner in the future. Any description of a riot or protest might have implied this to some unsympathetic readers. In the poem, in fact, the only reason teargas is fired is to extract some form of knowledge from the crowd – namely, dreams. It is not fired because of a previous act. The commodity status of teargas, a weapon which some people supply in order to make a profit, is foregrounded in this poem.40 It is probably already clear from the coordinates I’ve set up why the poem would claim that teargas ‘is the anti-Rimbaud’. Someone subjected to teargas, as Anna Feigenbaum states, ‘can think of nothing but relieving his own distress.’41 Pain individuates the protestor. Teargas can reach every member of a crowd, unlike a bullet, which typically hits an individual. Teargas was designed and developed to isolate the individual from the mob spirit. It is in this sense that it is the ‘absolute regulation and administration of all the senses’.

There is a topography to ‘What Teargas is For.’42 In its map, the police fire teargas at a crowd, who must be at a certain distance from them. Somewhere else is the Non-Executive Chairman of the company which manufactures and sells that teargas, and Charles Windsor, the Prince of Wales. The poem states that ‘He’ believes that teargas is like the cloud of unknowing. Since the previous sentence mentions two male figures, it is unclear if ‘He’ is Charles Windsor or the Non-Executive Chairman. This lack of clarity is only the first instance in this poem of blurring, smudging, imprecision, or vaguening. Insofar as the cloud of unknowing is something experienced by an initiate as they approach God, we might say that the administration of pain through teargas to the crowd produces the distance between the crowd and Charles Windsor or the Non-Executive Chairman. We might say that the imposition of this cloud on the crowd, who are perhaps in the process of discovering their own power, produces a deification of those figures, who are not in power in any prior sense, but only in power insofar as the teargas they make is imposed on that crowd. As Ross observes of Rimbaud’s work, space is not as a ‘static reality’ in ‘What Teargas is For’ but ‘active, generative’ and we as readers ‘experience space as created by an interaction.’43 To echo Will Alexander’s epigraph to this essay, the teargas forms a table at which judges, Non-Executive Chairmen, Prince Charles, and executioners sit.

The weird spatializations produced by teargas have also been described by Dariouche Tehrani, who emphasizes the everydayness of teargas. Tehrani points out that debates about where teargas is deployed produce a particular conception of space, one in which the sacred and profane are attributes of different areas. Tehrani discusses the deployment of teargas inside or around a mosque in Paris in 2005. The difference between ‘inside’ or ‘around’ is not important for Tehrani, who seeks to estrange the ostensibly ‘humanitarian’ nature of teargas and also grasp the vaguening of locale or boundary implicit in the use of such a dispersed weapon. For Tehrani, the question of whether the teargas thrown into the mosque, or deployed elsewhere and that happened to blow in, is only important for a Western secular humanism which seeks to legally justify the imposition of pain on colonized peoples in a profane space. Acknowledging that it is ethically wrong to deploy teargas in a sacred space merely justifies its use elsewhere.44 We might say with Tehrani that in the poem the deployment of teargas on the crowd sacralises whatever space Prince Charles and the Non-Executive Chairman occupy.

Just as there is a topography, there is a topology to this poem and to Bonney’s language-use more generally, because Bonney’s poetry is constantly studying what is preserved and what is altered under continuous deformations like stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending, which is another way of saying it studies what remains the same and what changes under duress. This poetry shows us how words and meanings are subject to such duress, how their valence might change even if their letters stay the same. This is dramatized in these poems when meanings and words shift according to whether it is an enemy’s understanding of the meaning or another meaning that is at work, if sometimes hidden in its ‘kernel’. Take, for example, ‘Our Death 27 / Under Duress’, whose enemy is not Charles Windsor but Steve Bannon. The poem ends with another clear us vs. them situation: ‘Remember this. Our word for Satan is not their word for Satan. Our word for Evil is not their word for Evil. Our word for Death is not their word for Death.’45 Echoing this, we might say that, in ‘What Teargas is For’, our word for ‘Unknowing’ is not their word for ‘Unknowing’, our ‘mysticism’ is not their ‘mysticism’, our ‘knowledge’ is not their ‘knowledge’.

The word ‘knowledge’ becomes a site of contestation in ‘What Teargas is For’ in the following way. The poem mentions the pain of teargas, then says that knowledge is ‘Unknowing’, for the cops at least. What the police call ‘knowledge’ is the knowledge which the blunt force trauma of a teargas cannister to the head removed from Lobna Allami.46 That is to say that what the police call knowledge is the negation of the crowd’s knowledge. What is knowledge for one side is unknowing for another. This knowledge or unknowing is then referred to in ‘What Teargas is For’ as ‘it’ a few times. The ‘it’ becomes a contentious superposition of knowledge and unknowing. They are unstable: words and their various meanings are sites of class struggle. This has echoes with Rimbaud’s work, as Ross tells us that in Rimbaud, just as in Bonney’s ‘Letters’, and in the communal surround they emerge from, what is slander for some becomes a rallying cry for others.47 Bonney’s work draws on a model of language in which there is an inside and an outside, an esoteric secret concealed beneath a surface, which is always at play in antagonism or in situations where there are initiates and non-initiates, enemies and friends. And just as in ‘Letter on Harmony and Sacrifice’, knowing and understanding are the product of a projectile weapon – a teargas cannister or a bullet.

Antagonism is also brought to the fore in the poem by namechecking contentious figures open to multiple interpretations. Bonney’s poem mentions Lou Reed’s divisive album Metal Machine Music (1975): more specifically, its ‘sleeve notes’. Reed claimed he made the album as a ‘giant fuck-you’ to a certain contingent of his fans, those who would go to gigs and request his most popular and radio-friendly songs, and the liner notes state: ‘Most of you won’t like this and I don’t blame you at all.’48 Similarly, Bonney knows that when he discusses Blake’s work, we need to keep in mind, as ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ tells us, that Blake might be read as a mystic, a left-wing radical revolutionary, or an ‘emblem of English nationalism.’49 Interpretational antagonism is not just embedded in words like understanding and knowledge, but in the proper names Reed and Blake and Rimbaud.

One way to get away from this problematic of knowledge and understanding might be to use terms which are less prone to misunderstanding.50 But Bonney refuses to relinquish words which are prone to the enemy’s understanding. If Bonney refuses to abandon those words, he remains hyper-aware of the fact that their definitions and what we understand by them are a site of struggle. We cannot begin to read Bonney’s work adequately if we do not attend to the fact that his work is constantly transforming the words it is using, flipping their meanings on their heads and trying to get at their undercurrents and reveal their obscured histories, reminding us constantly of their context to shift their content, using sociality and discussion to explore what can be changed in our words, how we can avoid the simple meaning ascribed to them in what one of the ‘Letters’ calls ‘the dictionary of the visible world.’51 When we read Our Death (2019), we must remember that the meaning of death is a site of contestation and community-formation: ‘Our word for Death is not their word for Death.’52

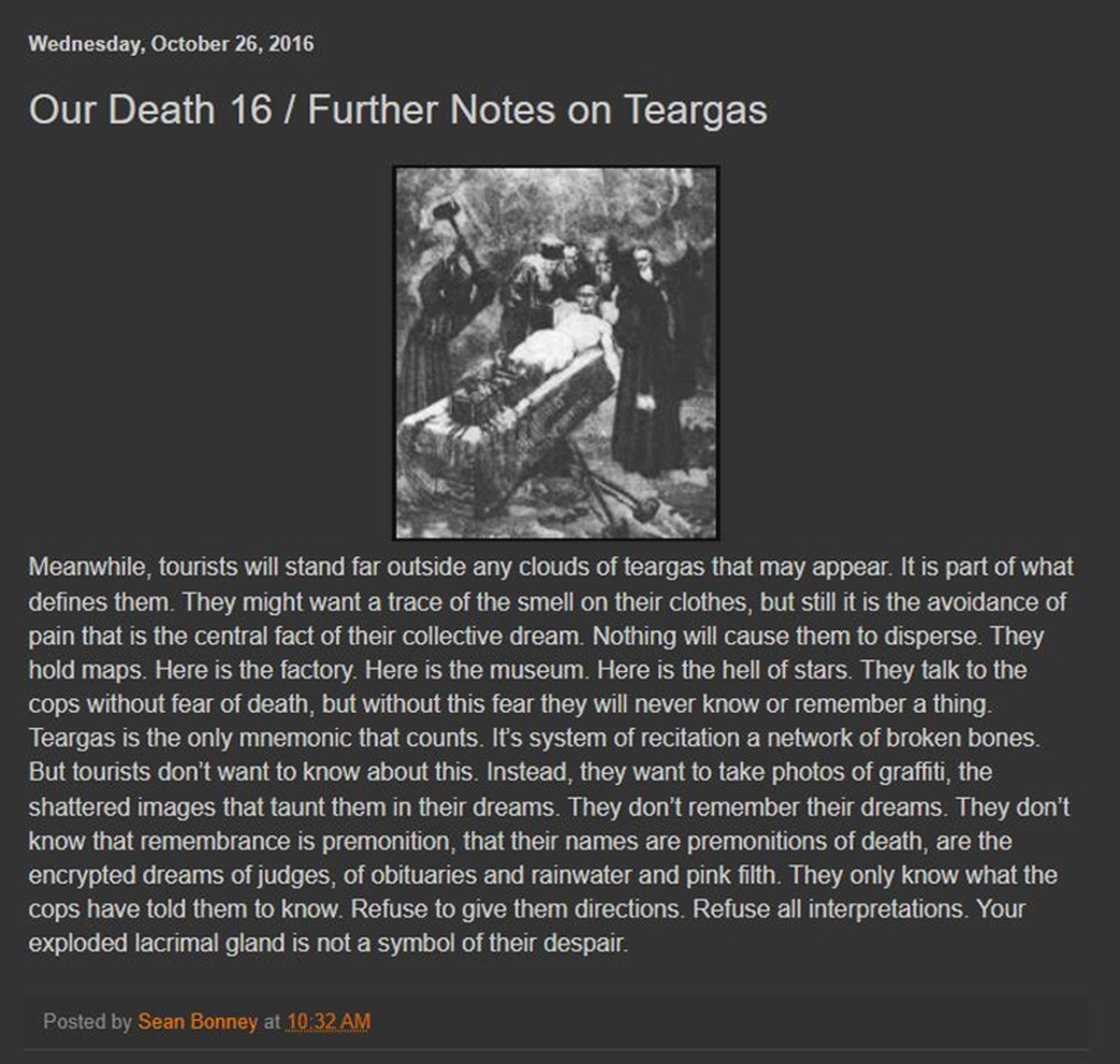

On his blog abandonedbuildings, Bonney often posted images accompanying his texts. The image posted with ‘Our Death 16 / Further Notes on Teargas’ on 26th Oct. 2016 was originally from a website called Medieval Warfare (see Fig. 2, below). The image was originally captioned thus: ‘Urbain Grandier was tortured by having his lower legs smashed in a boot, having been convicted of trumped-up charges by a Cardinal and an Abbess.’53 The ‘boot’ is a family of instruments of torture and interrogation designed to crush the foot and leg. It was widely employed throughout Europe both to extract information and to force prisoners to confess to crimes whether they committed them or not. I wonder if what is pictured here is what Will Alexander calls the ‘iron leggings wrought by the bondage of logicians’, or what Bonney in the previous poem called ‘the absolution regulation and administration of all the senses.’54 Torture is partly about the extraction of knowledge, and it is tempting to twist this and say it is about the production of knowledge too. Urbain Grandier is being tortured to be taught a lesson. He is being taught not to get on the wrong side of Cardinals and Abbesses, and what is being done is also intended to serve as an example to others about what might happen to them. This keeps Cardinals and Abbesses in power. Bonney chose this image because he is not distracted by the change in Public Relations that teargas elicits, as Anna Feigenbaum’s work shows so clearly and carefully: he knows teargas is torture, nothing less.

The tortured artist is another iteration of the poète maudit, a complicated trope which is analysed in many of the ‘Letters’. In his essay ‘Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City’, for example, Bonney discusses Amiri Baraka’s critique of the notion of the ‘tortured genius’, drawing attention away from the aestheticized figure of suffering and towards the personified and sometimes impersonal forces doing the torturing. The relevant passage from Baraka’s Dutchman (1964) runs as follows: ‘Charlie Parker? Charlie Parker. All the hip young white boys scream for Bird. And Bird saying “Up your ass, feeble-minded ofay! Up your ass”. And they sit there talking about the tortured genius of Charlie Parker. Bird would’ve played not a note of music if he just walked up to East Sixty-Seventh Street and killed the first ten white people he saw.’55 In a discussion of this quote, Bonney states: ‘In response to the bohemian clichés about the “tortured genius” we ask who is it doing the torturing, and would it not be better to take revenge on that torturer than for Bird to transmute the wounds of that torturing into the beauty of his music.’56 The ‘mystical shell’ I have been touching on might return here as a conch, a wind instrument for Baraka’s Charlie Parker. But it is also the boot, the a percussive instrument of torture in the image accompanying ‘Further Notes on Teargas’ (see Fig. 2) – a shell whose allegedly ‘rational’ kernel is mangled flesh. This chimes with ‘Further Notes on Militant Poetics’, which says that the ‘rational kernel’ of ‘poetic mysticism’ is two things: the lives of the oppressed, exemplified by ‘benefit claimants’ and ‘migrant workers’, and capital’s ‘inner workings’, which are ‘partially’ glimpsed in the details of ‘the lives of the very rich’. The rich and powerful, the executive chairman and Charles Windsor, generate and maintain their wealth not only through exploitation of labour but direct application of pain.57 Bonney’s teargas poems ask us to ask who is doing the torturing, and for who. The poem and the image remind us that, although we can discuss what is happening at a protest in terms of a set of complex, abstracted phenomena occurring behind our backs, there are real people with names accruing immense pleasure and wealth from this pain in the really existing feudalism of the United Kingdom. It will not let us forget this.

In ‘Our Death 16 / Further Notes on Teargas’, the mapping from the earlier ‘What Teargas is For’ is complexified, as ‘tourists’ are added to the equation. The piece ends with the following declaration: ‘Your exploded lacrimal gland is not a symbol of their despair.’58 The remnants of the reader’s ruined lacrimal gland, which produces tears, does not represent a victory against ‘them’. Your burst tear ducts are not some metaphor for the pain of the text’s enemy. I think of Symbolism again. Bonney’s Baudelaire, his Rimbaud. At the close of the poetic diptych, Bonney refuses knowing what is inside the mystical shell. But it seems to me that the whole logic of the symbol is refused; there is no symbol of anything, and there is no way of transforming suffering at the hands of the ruling classes into the ruling classes’ despair. The immiseration thesis cannot apply. If that exploded gland is not a symbol it might be a cymbal, an instrument to be played in a non-instrumental manner, a note to be heard or played around with and ruminated on in collective mourning. The ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ and the sleeve notes to Metal Machine Music and ‘Further Notes on Teargas’ all attempt to describe or transform noise, approaching cacophony as they mingle disparate threads of thinking together. The notes approach the noise they can only ever paper over. Bonney’s notes, and my own offered here, are not some harmonic regime fixed in ivory. They are meant to be bent as they are played.

Notes

- Sean Bonney, ‘Further Notes on Militant Poetics’, 27th Sept. 2013, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2013/09/further-notes-on-militant-poetics.html. [^]

- Sean Bonney, ‘Letter Against Hunger / A Foodstamp for the Palace’, 29th July 2013, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2013/07/letter-against-hunger-foodstamp-for_3165.html; Sean Bonney, Letters against the Firmament (London: Enitharmon, 2015), pp. 95–97. [^]

- Will Alexander, Sunrise in Armageddon (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2006), p. 66. This essay will follow Sean Bonney by using the single word ‘teargas’ in the body text and ‘tear gas’ as and when a quotation or book title opts for this choice. [^]

- I am thinking of ‘Poetry and Revolution’, held in May 2012, and ‘Militant Poetics’, held in May 2013, at Birkbeck College. Some of the papers and responses to the latter can be found here: http://militantpoetics.blogspot.com/. See also https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2013/08/poetry-and-or-revolution-conference-to-be-held-oct-3-5-in-the-bay-area. [^]

- Danny Hayward, Wound Building: Dispatches from the Latest Disasters in UK Poetry (Earth, Milky Way: punctum, 2021), p. 191. [^]

- Sean Bonney, ‘Letter Against the Language’, 12th January 2016, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2016/01/letter-against-language.html. Sean Bonney, Our Death (Oakland, CA: Commune Editions, 2019), p. 18. The screenplay is Pasolini, Saint Paul: A Screenplay, trans. Elizabeth A. Castelli (London: Verso, 2014). The essay mentioned later is ‘What Is This Coup? I Know’, trans. Pasquale Verdicchio, in In Danger: A Pasolini Anthology, ed. Jack Hirschman (San Franscisco, CA: City Lights, 2010), pp. 225–232. [^]

- The speaker of the ‘Letters’ is a complicatedly lyrical, autobiographical, and intertextual persona which constantly courts being conflated with Sean Bonney himself – and some critics have taken the bait. See, for example, Andrea Brady ‘Sean Bonney: Poet Out of Time’, Communism and Poetry: Writing Against Capital, ed. Ruth Jennison and Julian Murphet (London: Palgrave, 2019), pp. 131–159: pp. 144–5. This is a constant danger in discussing Bonney’s work, and I may also have fallen foul of it above. The question of how close the persona and the author can be conflated is material which the ‘Letters’ themselves toy with, but it is difficult to hold the position that the ‘Letters’ are direct statements of Bonney’s thoughts (as Brady does) when they contain so many silent and unmarked borrowings. It is not the case, nor would Brady claim, for example, that Bonney stayed up one night electrocuting dogs with alternating and direct current: ‘[W]hat about that night when we electrocuted a number of dogs. Remember that? By both direct and alternating current? To prove the latter was safer?’ Sean Bonney, ‘Letter on Riots and Doubt’, 5th Aug. 2011, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/08/letter-on-riots-and-doubt.html, and Letters Against the Firmament, pp. 8–9. This is something which was done by individuals such as Harold Brown during the war of the currents in the nineteenth century. See Jill Jonnes, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World (New York: Random House, 2003), pp. 172–5; Richard Moran, Executioner’s Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair (New York: Vintage, 2002) pp. 97–100. There are of course utterances in the ‘Letters’ which look rather like opinions held by a committed anarcho-communist author, and statements which might indeed describe Bonney’s personal life, but those must always be considered as occurring in the same field or level as this kind of sampling or mixing of the speaker with Harold Brown. [^]

- Brady has suggested that Bonney should write sound poetry in the vein of M. NourbeSe Philips’ Zong! (2008) (p. 152). However, not only is Bonney’s project completely different from Philips’ Zong!, but, as I have just suggested, Our Death contains a proleptic response to this critique. Bonney considered sound poetry to be too safe a haven in the British Poetry Revival context, indeed considered it just as racially ‘privileged’ as Brady considers ‘clear enunciation’ (p. 152). As I imply above, sound poetry after the British Poetry Revival and in its lineage, might just be the ‘comfortably opaque experimental poetry’ ‘Letter Against the Language’ gestures at. The point of cleaving to ostensibly clear language (and I hope the body of my essay will show just how complicated and subject to duress that allegedly clear language is) was precisely to make his audience uncomfortable, the kind of discomfort which is registered by the opening of Brady’s essay (see p. 132). [^]

- Sean Bonney, ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 1/3’, 15th Mar. 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/03/notes-on-militant-poetics-1-3.html. [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 1/3’; ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2/3’, 27th Mar. 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/03/notes-on-militant-poetics-23.html; ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.5/3’, 14th Apr. 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/04/notes-on-miltant-poetics-25-3.html; ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.9/3’, 13th May 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/05/notes-on-militant-poetics-29-3.html; ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 3/3’, 1st July 2013, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/07/notes-on-militant-poetics-33.html; ‘Further Notes on Militant Poetics’. The ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ were published together on 15th June 2018 at https://my-blackout.com/2018/06/15/sean-bonney-notes-on-militant-poetics/. [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.9/3’, 13th May 2012. Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (Middlesex: Penguin, 1970). Of particular importance to Bonney’s text is Jean Genet’s introduction in that volume. [^]

- To give one example, ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.9/3’ quotes Edouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse, trans. J. Michael Dash (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1999), p. 123, and the same sentences are also discussed in ‘Baraka and Surrealism’, 26th July 2019, https://notesonbaraka.blogspot.com/2019/07/baraka-and-surrealism.html. and ‘Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City,’ 26th July 2019, https://notesonbaraka.blogspot.com/2019/07/non-cognitive-aspects-of-city.html. This quote also appears in Sean Bonney, Happiness: After Rimbaud (London: UnKant, 2011), p. 55. ‘Notes on Militant Poetics’ and the ‘Letters’ and the ‘round midnight’ blog also share much material with his PhD thesis, Tensions Between Aesthetic and Political Commitment in the Work of Amiri Baraka (PhD, 2012), which Robert Hampson’s essay in this cluster discusses in greater detail. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Baraka and Surrealism’, 26th July 2019, https://notesonbaraka.blogspot.com/2019/07/baraka-and-surrealism.html. The essays published on this blog are concerned with African-American spiritual traditions which can be characterized as esoteric. [^]

- Leigh Wilson, Modernism and Magic: Experiments with Spiritualism, Theosophy and the Occult (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), p. 1. [^]

- An example of ‘magic’ being used in an anticapitalist context might be Sarah Jaffe, ‘All Organizing is Magic’, 25th Oct. 2019, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4465-all-organizing-is-magic, which emphasizes the positive figure of the witch. The word ‘magistrate’ is derived from the same root as magic, magi-, and Bonney’s work often features them as magicians of capital. The best example of this is ‘First Letter on Harmony’, 11th Nov. 2011, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/11/first-letter-on-harmony.html. [^]

- Although ‘Letter on Poetics (after Rimbaud)’ refuses the term ‘magic’ (‘I’m not talking about the poem as magical thinking, not at all, but as analysis and clarity.’), it does keep coming up in the ‘Letters.’ 25th June 2011, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/06/letter-on-poetics.html. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 3/3’. For explicit discussions of The Daily Mail, see ‘Letter Against the Firmament’, 8th Sept. 2014, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2014/09/letter-against-firmament.html. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.9/3.’ [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2/3’. [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.5/3’. [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2/3’. See also: ‘the internal secret of bourgeois poetics is the voice of the oppressed and dispossessed’. ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 2.9/3.’ [^]

- In the essay ‘Time Negatives of Variable Universe’ Bonney describes ‘static’ as ‘the sound of the enemy jamming our signals’ as well as ‘the sound of our own thinking as it moves outside of what official language permits.’ Bonney, ‘Time Negatives of Variable Universe’, 26 July 2019, https://notesonbaraka.blogspot.com/2019/07/time-negatives-of-variable-universe.html. One of the ‘Poems after Katerina Gogou’ (2015), speaking of a hopeful future, says: ‘There will be no locked doors. / No officials, no murders, no slaves. / Sometimes we’ll speak in colours, / in musical notes.’ ‘Poems after Katerina Gogou’, 24th Sept. 2015, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2015/09/poems-after-katerina-gogou.html. All This Burning Earth: Selected Writings of Sean Bonney (Ill Will Editions, 2016), p. 57. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Further Notes on Militant Poetics’. Compare Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 1, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 201–21: p. 211–2; Karl Marx, Capital Volume One, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 103. ‘Second Letter on Harmony’ riffs on this: ‘Once, revolutions took their poetry from the past, now they have to get it from the future. We all know that. Famous and so on. In its contemporary form, the slogan Greek anarchists were using a couple of winters ago: we are smashing up the present because we come from the future. I love that, but really, it’s all just so much mysticism: but if we can turn it inside out, on its head etc we’ll find this, for example: ‘the repeated rhythmic figure, a screamed riff, pushed its insistence past music. It was hatred and frustration, secrecy and despair … That stance spread like fire thru the cabarets and the joints of the black cities, so that the sound itself became a basis for thought, and the innovators searched for uglier modes’. That’s Amiri Baraka, a short story called ‘The Screamers’ from 1965 or something like that.’ (Bonney, ‘Second Letter on Harmony’, 16th Dec. 2011, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/12/second-letter-on-harmony.html. Bonney, Letters against the Firmament, p. 33–6.) The slogan is mystical in the pejorative sense (‘just so much mysticism’) until it is inverted, turned on its head, to find a sentence from Baraka. See The Amiri Baraka Reader, ed. William J. Harris (New York: Basic Books, 1991), pp. 171–6. [^]

- Marx, Capital, Volume One, p. 103. [^]

- Ibid, p. 972, p. 973, p. 1001. [^]

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987), p. 320. [^]

- Fred Moten, Stolen Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), pp. 1–2. [^]

- Moten, Stolen Life, p. 4. [^]

- I try to use the term ‘Letters’ as opposed to italicized Letters to refer to all the ‘Letters’ from ‘Letter on Poetics’ (2010) up to ‘Letter Against the Language’ (2016), as if they are a single serial project, as distinct from the book Letters Against the Firmament, which contains some of the ‘Letters’ alongside other texts. There are many places in the ‘Letters’ where the relation between knowing and not knowing is reconfigured. ‘Letter on Riots and Doubt’ (2011) begins: ‘A while ago I started wondering about the possibility of a poetry that only the enemy could understand. We both know what that means.’ (Bonney, ‘Letter on Riots and Doubt’, 5th Aug. 2011, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/08/letter-on-riots-and-doubt.html. Bonney, Letters against the Firmament, pp. 8–9.) As Keston Sutherland points out, ‘The ‘enemy’ is not identified, but it seems clear that it is ourselves.’ (Sutherland, ‘Sean Bonney’s Hate Poems’, Post45 (2019), n22. https://post45.org/2019/07/sean-bonneys-hate-poems/.) At times, Bonney includes himself in the category of enemy bourgeois – for example ‘Letter Against the Language’ (2016) says: ‘Like the bourgeois I am I went looking for a bus-stop.’ (Bonney, ‘Letter Against the Language’, 12th Jan. 2016, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2016/01/letter-against-language.html. Our Death, p. 19). [^]

- ‘Letter on Harmony and Sacrifice’, 31st Jan. 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/01/letter-on-harmony-and-sacrifice.html. Letters against the Firmament, pp. 37–9. [^]

- Rudyard Kipling, Selected Poems, ed. Peter Keating (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 134–5. [^]

- Jacob Bard Rosenberg, ‘Notes to Sean Bonney (1969–2019), https://prolapsarian.tumblr.com/post/189486233632/notes-to-sean-bonney-1969-2019. [^]

- The Association of Musical Marxists, prominent members of which were Ben Watson and Andy Wilson, note in their manifesto printed at the back of Happiness: Poems After Rimbaud that they are tired of being treated as ‘soppy mystics.’ Bonney, Happiness: Poems After Rimbaud (London: UnKant, 2011), p. 73. In the Manifesto they proclaim the music of John Coltrane to be ‘a PLAN OF ACTION, A PRINCIPLE OF LIFE and a CRITICISM OF BUSINESS AS USUAL.’ In ‘Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)’, Fred Moten speaks of ‘Trane’s mysticism,’ which he says is ‘the polyvalent collectivity of his constant worrying of beginning’ (Fred Moten, ‘Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)’, p. 767). [^]

- Bonney mentions the Kristin Ross book in ‘Interview with Sean Bonney’, The Literateur 10th Feb. 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20190509112645/http:/literateur.com/interview-with-sean-bonney/: ‘A lot of Rimbaud comes directly out of the Paris Commune in 1871, there’s a very good book by Kristin Ross that argues just that.’ [^]

- Bonney, ‘Letter on Poetics (after Rimbaud)’, 25th June 2011, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/06/letter-on-poetics.html. Bonney, Letters against the Firmament, pp. 140–143. See Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters, a Bilingual Edition, trans. Wallace Fowlie, ed. Seth Whidden (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005), pp. 370–1. [^]

- Marx, Capital, Op.Cit, pp.102–103. [^]

- Police brutality is a recurrent concern in Bonney’s ‘Letters.’ Numerous victims are named. Mark Duggan is mentioned in ‘Letter on Silence’, 30th Aug. 2011, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/08/letter-on-silence.html, ‘Letter on Harmony and Sacrifice’, 31st Jan. 2012, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2012/01/letter-on-harmony-and-sacrifice.html, and ‘Letter Against the Firmament / A Treatise on Mathematics’, 21st Oct. 2014, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2014/10/letter-against-firmament-treatise-on.html?m=0. Jacob Michael, a victim of a police beating, is also mentioned in ‘Letter on Silence’, 30th Aug. 2011, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/08/letter-on-silence.html. See Letters Against the Firmament, pp. 12–3; pp. 37–9; pp. 106–7. [^]

- Sean Bonney, ‘Our Death 12 /// What Teargas is For’, 1st Oct. 2016, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2016/10/letter-in-turmoil-12-what-teargas-is-for.html. Bonney, Our Death, p. 73. Ted Rees offers wonderful glosses on this poem in ‘In Memoriam: Sean Bonney, 1969–2019’, The Poetry Project Newsletter #260 — Feb./Mar./Apr. 2020, https://www.poetryproject.org/publications/newsletter/260-feb-march-april-2020/in-memoriam-sean-bonney-1969-2019. [^]

- ‘For the first time you do it, you will find only a darkness, and as it were a cloud of unknowing […] Whatever you do, this darkness and the cloud are between you and your God, and hold you back from seeing him clearly by the light of understanding in your reason and from experiencing him in the sweetness of love in your feelings.’ The Cloud of Unknowing and Other Works, trans. A. C. Spearing (London: Penguin, 2001), pp. 22. [^]

- Bonney also talks about rioters getting trapped into the commodity form in the very act of rioting: ‘The main problem with a riot is that all too easily it flips into a kind of negative intensity, that in the very act of breaking out of our commodity form we become more profoundly frozen within it. Externally at least we become the price of glass, or a pig’s overtime.’ (‘Letter on Riots and Doubt’, 5th Aug. 2011, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2011/08/letter-on-riots-and-doubt.html.) Compare: ‘Real-life riots and mass civil disobedience were the best marketing demonstrations that manufacturers could hope for.’ Anna Feigenbaum, Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of WWI to the Streets of Today (London: Verso, 2017), p. 92. [^]

- Feigenbaum, Tear Gas, p. 28. [^]

- By invoking topography I am drawing on Kristin Ross’ characterisation of Rimbaud’s work as engaging in ‘social topography.’ Ross, The Emergence of Social Space, p. 40. [^]

- Ross, The Emergence of Social Space, p. 35. [^]

- Dariouche Tehrani, ‘The Colonial Gas Machine: Teargas Grenades, Secular Humanist Police, and the Intoxication of Racialized Lives’, Verso Blog 30th Nov. 2017, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3507-the-colonial-gas-machine-teargas-grenades-secular-humanist-police-and-the-intoxication-of-racialized-lives. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Our Death 27 / Under Duress’, 2nd Feb. 2017, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2017/02/our-death-27-under-duress.html. Our Death, p. 96. [^]

- Feigenbaum, Tear Gas, p. 3. [^]

- Ross, The Emergence of Social Space, pp. 148–9. [^]

- Victor Bockris, Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story (London: Harper Collins, 2014), p. 283. [^]

- ‘Notes on Militant Poetics 3/3.’ [^]

- Rather than relying on words like ‘knowledge’ and ‘understanding’, with all their baggage, these texts might have turned to ‘study’, as put forward by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney. For Moten and Harney, the problems associated with the word ‘knowledge’ necessitate terminological shifts: they speak of study as a process rather than knowledge as an object. See, for example, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions, 2013), p. 110. [^]

- In ‘Letter Against the Language’, Bonney discusses the meaning of the word ‘communism’ by way of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Teorema (1968): ‘the scene at the end of Theorem, where the father – having given his factory away to the workforce, and then having tried and failed to pick up a boy at a railway station, takes off his clothes and wanders off into some strange volcanic or desert landscape and, as he enters that landscape, he screams. I was ranting on to a friend a few days ago that I take that scream to contain all that is meaningful in the word ‘communism’ – or rather, what it is that people like us mean when we use that word which is, as we both know all too well, somewhat different to whatever it is the dictionary of the visible world likes to pretend it means. You know what I’m saying. A kind of high metallic screech. Unpronounceable. Inaudible.’ (Bonney, ‘Letter Against the Language’, 12th Jan. 2016, https://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2016/01/letter-against-language.html. Sean Bonney, Our Death, pp. 17.) [^]

- Bonney, ‘Our Death 27 / Under Duress’. Our Death, p. 96. [^]

- ‘Medieval Torture’, https://www.medievalwarfare.info/torture.htm. [^]

- ‘In Conversation | Will Alexander & James Goodwin’, Granta, 4th Jan. 2022, https://granta.com/in-conversation-goodwin-alexander. [^]

- The Amiri Baraka Reader, ed. William J. Harris (New York: Basic Books, 1991), pp. 76–99: p. 97. [^]

- Bonney, ‘‘Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City.’’ [^]

- ‘They have watched as their products are used to kill, maim, and torture people around the world. They have bought new houses, seen their children off to school, perhaps spent $150,000 at a Christie’s auction to acquire historic souvenirs. Investigating the financial lives of the elite is crucial for understanding how the security industry operates. Riot control is, and always has been, in the business of protecting the wealth of a tiny minority.’ Feigenbaum, Tear Gas, p. 166. [^]

- Bonney, ‘Our Death 16 / Further Notes on Teargas’, 26th Oct. 2016, http://abandonedbuildings.blogspot.com/2016/10/letter-in-turmoil-16-further-notes-on.html. Our Death, p. 97. [^]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Azad Ashim Sharma and Jeff Hilson for comments on an earlier draft. David Grundy’s comments on several drafts have been indispensable. Thanks also to my two anonymous peer reviewers.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.